CoastSnap Delaware

Using smartphones and crowd sourcing to monitor the dynamics of Delaware Beaches

CoastSnap DE is a local program that is part of a larger global community science project to capture our changing coastlines. With three sites in Delaware to choose from, if you have a smartphone and an interest in the coast, we welcome you to participate!

CoastSnap relies on repeat photos at the same location to track how the coast is changing over time due to processes such as storms, rising sea levels, human activities and other factors. Using a specialised technique known as photogrammetry, CoastSnap turns your photos into valuable coastal data that is used by coastal scientists to understand and forecast how coastlines might change in the coming decades. Photogrammetry enables the position of the coastline to be pinpointed from your snaps to an accuracy similar to that of professional coastal survey teams. All we ask is that you take the photos at the same location (by using one of our official CoastSnap DE camera cradles o and send us the photo. There are a variety of options available from a free App to using email or social media such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook record the precise photo time in the App. The more photos we have of a particular site, the better our understanding becomes of how that coastline is changing over time.

Using a specialised technique known as photogrammetry, CoastSnap turns your photos into valuable coastal data that is used by coastal scientists to understand and forecast how coastlines might change in the coming decades. Photogrammetry enables the position of the coastline to be pinpointed from your snaps to an accuracy similar to that of professional coastal survey teams. All we ask is that you take the photos at the same location (by using one of our official CoastSnap DE camera cradles and send us the photo. There are a variety of options available from a free App to using email or social media such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook record the precise photo time in the App. The more photos we have of a particular site, the better our understanding becomes of how that coastline is changing over time.

In recent years, widely-available smart phone technology has developed quickly to include meter-scale georeferencing capability and photograph resolutions upwards of 10 mega-pixels (Harley et al., 2019). Often, after an extreme storm event, concerned members of the public will document morphology changes using photographs, but these photographs are rarely shared with beach management personnel or academic scientists. This project seeks to leverage the wide availability of this technology among interested members of the public by setting up three beach monitoring sites on the Delaware coast. Users would place their smart phone in an installed cradle take a photograph, and then upload this photo to social media using a specified hashtag, where it can be downloaded by the investigators for inclusion in a photographic times series of that beach. This workflow will therefore help to facilitate data sharing between community scientists, beach management personnel, and academic scientists. By controlling the position and angle of the phone camera, we can then measure the shape and width of the beach using methods developed by Dr. Mitchell Harley at the University of New South Wales Australia (Harley et al., 2019; Splinter, Harley, and Turner, 2018). This project would be a local extension of the global CoastSnap program, which began in New South Wales, Australia in 2017 and has since expanded to locations in the United Kingdom, Spain, Netherlands, France, and Fiji.

Shoreline change monitoring is critical for safe and effective coastal management, particularly before and after a coastal storm. However, scientists and coastal managers are limited in their capacity to document shoreline change and therefore lack important temporal and spatial sampling.

This new Delaware CoastSnap program aims to leverage smartphone technology, installing cradles that position photographs taken by citizen scientists for repeatability allowing the science team to quantitatively measure shoreline position and beachface slope.

The photographs are uploaded by users on social media using site specific hashtags. PI’s then harvest these photographs and, using surveyed ground control points and advanced open source image-processing, process them to determine the location of the shoreline geographically.

CoastSnap has been successfully implemented and tested in Australia (Harley et al., 2019) and sites in Europe but only one other site in the US

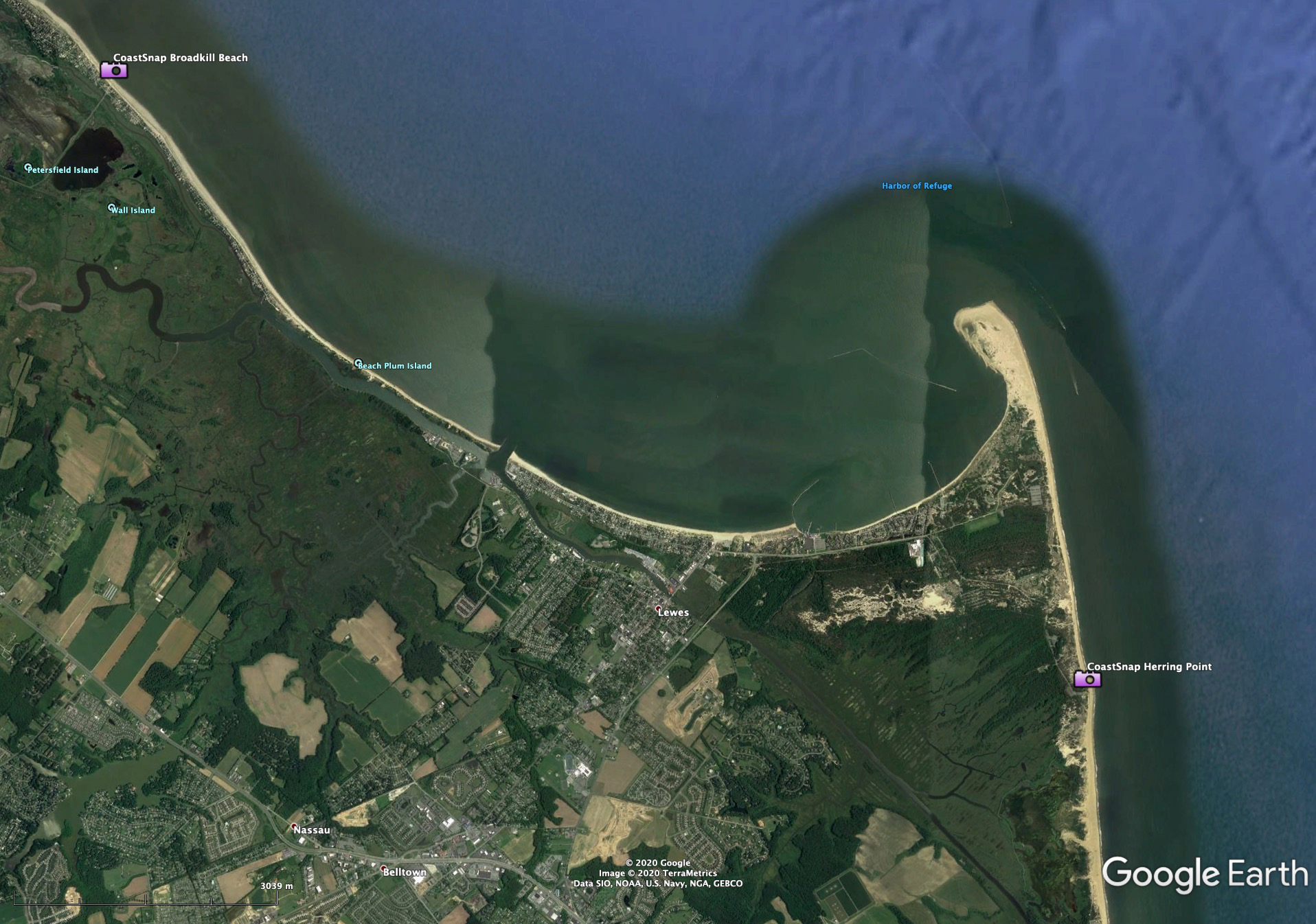

The project is establishing three CoastSnap sites on the Delaware Coast, including 2 on the Atlantic Ocean (Herring Point and Indian River Inlet) and 1 on the Delaware Bay Coast (Broadkill Beach). These sites were chosen in collaboration with the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) to align with their management issues and to provide a mix of coastal setting and morphodynamics (i.e. bay beach vs open ocean).

The utility of storm response monitoring has been shown in numerous studies internationally (Casella et al., 2014; Armaroli et al., 2012 and 2013; Harley et al., 2012; Short Trembanis,2004), nationally (Stockdon et al., 2007; Morton, 2002) and along the Delmarva (Nebel et al.,2012) and New Jersey shore (Nordstrom et al.,1992; Jackson et al.,2002 and 2010) and Delaware Bay (Dohner et al., 2016).

Tackling the coupled system of coastal morphology and storm response of the dynamic and highly varied coastal zone requires accurate, dense spatial and temporal data (Vos et al. 2019). This data is frequently unavailable both spatially and temporally due to the personnel, equipment, and time traditionally required to document coastal storm response (Harley et al. 2019).

Special thanks to Dr. Mitchell Harley, Scientia Fellow and Senior Lecturer in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering's Water Research Laboratory at University of New South Wales, the creator of the CoastSnap program. Dr. Harley graciously assisted and supported the creation of the CoastSnap DE app. To learn more about the overall CoastSnap program, visit the official website.

CoastSnap is as easy as slip, snap, share. Slip your camera phone into the cradle, snap a photo, and share it with us using any one of the convenient methods. CoastSnap sites are expanding and popping up at beaches around the world. Originally developed and tested in Australia now there are sites across the globe. Here in Delaware we are establishing 3 initial sites for this program. These sites are 1) Broadkill Beach 2) Herring Point in Cape Henlopen State Park and 3) Delaware Seashore on the south side of Indian River Inlet.

Herring Point in Cape Henlopen State Park is the site of two groins that were restored by DNREC in 2007 and 2008. Prior to restoration, erosion had exposed emergent tree stumps in the beachface, which significantly impacted the surf fishermen who frequently use the beach.

The management goals for this project were: 1) mitigation of bluff erosion in order to protect the historic (WWII) structures of Fort Miles; 2) enhancement of the popular recreational beach by increasing its width; 3) halting the degradation of the popular surfing break; 4) maintaining swimming quality by removing debris from the dilapidated groin structures and; 5) preserving recreational opportunities for surf fishermen (Powell and Mann, 2009). Within six months of their respective restorations, the fillets of both groins had filled to capacity and sand began bypassing the groins (Powell and Mann, 2009).

However, because of the popularity of the site for recreational users, surfers and surf fishermen, DNREC continues to monitor the downdrift beach that remains net erosive, despite bypassing (Powell and Mann, 2009). CoastSnap will allow more frequent monitoring of the width of the downdrift beach and complement the semi-annual surveys collected by DNREC while documenting quick-acting nearshore processes causing the downdrift erosion in spite of the groin bypassing.

Additionally, dune sediment and vegetation (visible in imagery) contribute to short-term dune processes, both physical and ecological, and will be examined through changing conditions within the year.

The south side of Indian River Inlet is an important site for the recreational opportunity it affords state park visitors, but also because it is the sand source for DNREC’s inlet sand bypassing system. The sand bypass system mimics natural net-northerly longshore transport that is currently blocked by the jetties at the inlet mouth (Keshtpoor et al., 2013).

Sand tends to accumulate behind the southern jetty, where the eductor pipe for the bypass system is deployed. Sand is pumped via pipe from the southern beach over the Indian River Inlet Charles W. Cullen Bridge to the depleted northern beach.

However, in 2015 and 2016, longshore sediment transport was net southerly, most likely due to “anomalous” wave conditions, and this resulted in resulted in reduced opportunity to manually bypass sediment (CB&I, 2017). These “anomalous” years have given DNREC more impetus to monitor the south side of the inlet to further refine the understanding of coastal processes in that area, and to develop operational alternatives to employ at the bypass plant for differing sediment transport conditions (CB&I).

The CoastSnap station on the southside of the inlet will give DNREC another “set of eyes” with capacity to quantify changes seen to help monitor the sand supply for their bypassing system between semi-annual surveys, as well as more frequent and more spatially-comprehensive monitoring of the beach conditions than the current semi-annual beach profiles allow. Adding to the shoreline and beach width tracking for this location is a nearby wave and current buoy operated by the US Army Corps of Engineers at Bethany Beach.

Accurate, shallow water wave measurements coupled with shoreline location, beach and dune morphology, and sediment volume transport calculations lends itself scientifically to decoding the “anomalous” wave conditions. This dataset further enables engineers to model sediment transport using actual location information as high spatial and temporal resolution for precise system understanding and thereby informed management decisions.

Broadkill Beach is a uniquely-managed site within the state of Delaware in that it represents the largest nourishment performed on the Delaware Bay shoreline (DNREC), through a one-time project partnership between the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Port of Philadelphia. The project was also unique in that the sand used to construct this beach was dredged from the main shipping channel of Delaware Bay.

DNREC is responsible for maintaining public access to this beach via a series of dune crossovers that are vulnerable to erosion during storms due to the proximity of the dune toe to the Bay. The CoastSnap site would help DNREC to gather “real-time” data on the condition of these crossovers and the width of the popular recreational beach below the crossover.

Long-term elevation data in the form of aerial imagery (plane, drone), aerial LiDAR, and DNREC RTK GPS profiles along with several years of nearshore bathymetric data at this site enables a detailed scientific analysis of this bay beach location. Estuary beaches around the world are the least studied type of system amongst coastal researchers and little data exists for how these low energy areas will respond to projected climate change impacts such as sea level rise, increased storm intensity, and land cover changes (i.e. saltwater marsh loss).

CoastSnap will add to the existing datasets (optical, elevation, morphological) at this site to enable investigations of long-term shoreline change here.